What Is More Powerful: God or Quantum Computing?

At first glance, this question might seem to invite an obvious answer—or perhaps no answer at all. Comparing the power of God to a technology feels like asking whether love is heavier than a mountain, or whether justice is faster than a cheetah. These are concepts that occupy different categories of existence entirely. Yet the question is worth taking seriously, because embedded within it are profound inquiries about the nature of power, the limits of technology, and whether human ingenuity can ever approach the divine.

The Category Problem

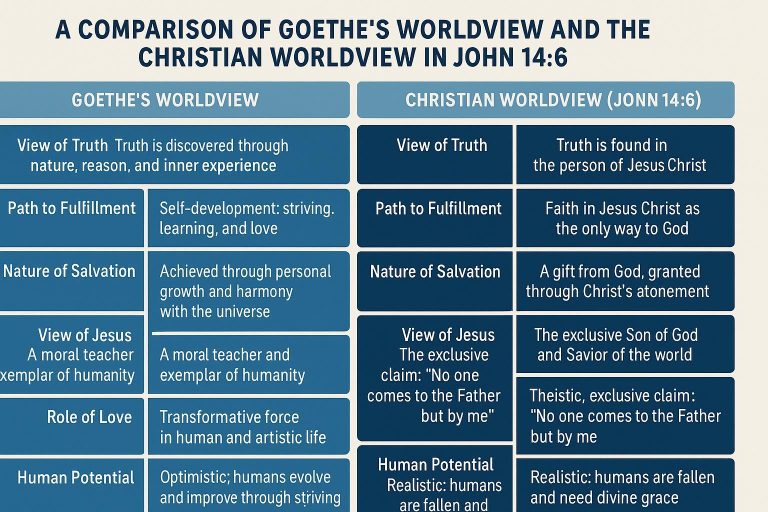

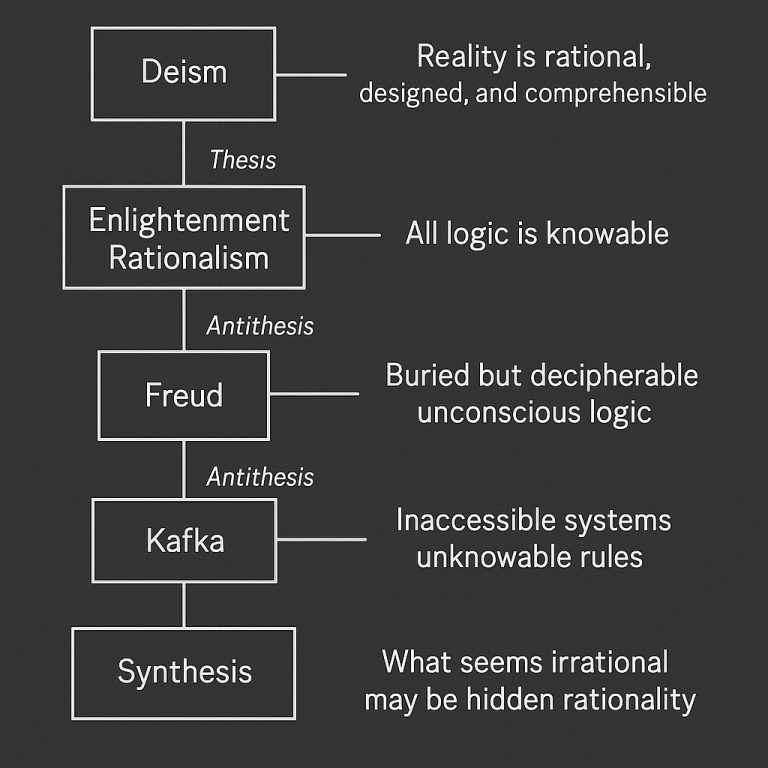

Before any meaningful comparison can be made, we must confront an immediate philosophical obstacle: God and quantum computing are not the same kind of thing. In classical theism—whether Jewish, Christian, Islamic, or certain strands of Hindu philosophy—God is understood as the ground of all being, the uncaused cause, the necessary existence upon which all contingent things depend. God is not a being among beings but Being itself, not powerful in the way a hurricane is powerful but rather the source from which the very concept of power derives its meaning.

Quantum computing, by contrast, is a technological artifact. It is a machine built by humans that exploits peculiar properties of quantum mechanics—superposition, entanglement, and interference—to perform certain calculations more efficiently than classical computers. It is impressive, revolutionary even, but it remains a tool. To ask whether a tool is more powerful than the source of all existence is, from a theological standpoint, to commit a category error of the highest order.

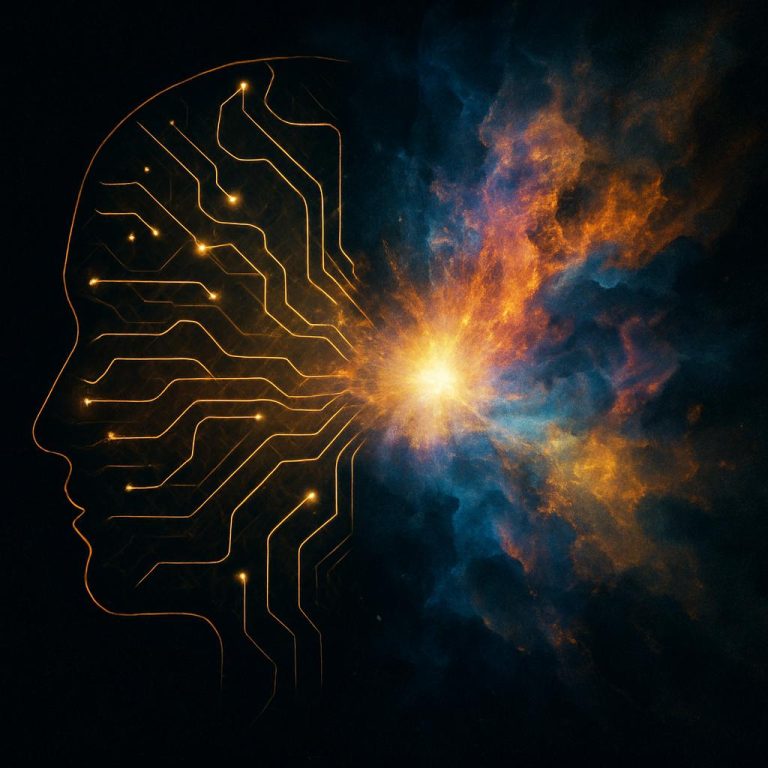

And yet, the question persists. Perhaps this is because in our technological age, the achievements of science and engineering have begun to feel godlike in their scope. We speak of artificial intelligence in quasi-religious terms, describe technology as “transcendent,” and wonder whether our machines might one day surpass all human limitations. Quantum computing, with its promise to solve problems that would take classical computers longer than the age of the universe, seems to push against the very boundaries of what is possible. Is it not, in some sense, reaching toward omnipotence?

What Quantum Computing Actually Does

To answer this, we need a clear-eyed understanding of what quantum computing actually is and is not. A quantum computer harnesses quantum bits, or qubits, which unlike classical bits can exist in superpositions of states. This allows quantum computers to explore many possible solutions simultaneously, making them extraordinarily effective for certain classes of problems: factoring large numbers, simulating molecular interactions, optimizing complex systems.

These capabilities are genuinely remarkable. Quantum computers may revolutionize drug discovery, materials science, cryptography, and artificial intelligence. They represent one of the most significant advances in computational theory since Turing’s original insights. But they are not magic, and they are not unlimited. Quantum computers are exquisitely sensitive to environmental noise, require temperatures colder than outer space, and remain extraordinarily difficult to scale. More fundamentally, they are still bound by the laws of physics, by logic, by mathematics. They cannot violate causality, create something from nothing, or transcend the fundamental constraints of the universe.

The Theological Conception of Divine Power

Compare this to the traditional conception of divine power. In classical theism, God’s omnipotence is not merely quantitative—not simply “a lot of power”—but qualitative and absolute. God is understood as the creator and sustainer of the physical laws that quantum computers must obey. The mathematics that makes quantum computing possible, the quantum fields from which particles arise, the very fabric of spacetime itself: all of these, in theological terms, are contingent upon divine creative will.

This framing suggests that asking whether God or quantum computing is more powerful is like asking whether an author or a character in their novel is more powerful. The character may be described as mighty within the story, but the author remains the source of the story’s existence. The character’s power is derivative; the author’s is original.

Moreover, divine omnipotence in its classical formulation includes capacities that no technology could possess: the power to create ex nihilo, to know all things past, present, and future, to exist necessarily rather than contingently, to be present everywhere simultaneously. Quantum computers, however advanced, remain local, temporal, contingent, and created. They depend on engineers, electricity, physical infrastructure, and the ongoing stability of natural law.

A Secular Counterpoint

Of course, not everyone accepts the premises of classical theism. For the atheist or agnostic, the comparison looks quite different. If there is no God, then quantum computing is not being compared to the ground of all being but to an idea, a human projection, a cultural construct. From this perspective, quantum computing is clearly more powerful because it actually exists and demonstrably does things. It solves problems, produces results, and advances human knowledge. A nonexistent God, however conceptually grand, has no power at all.

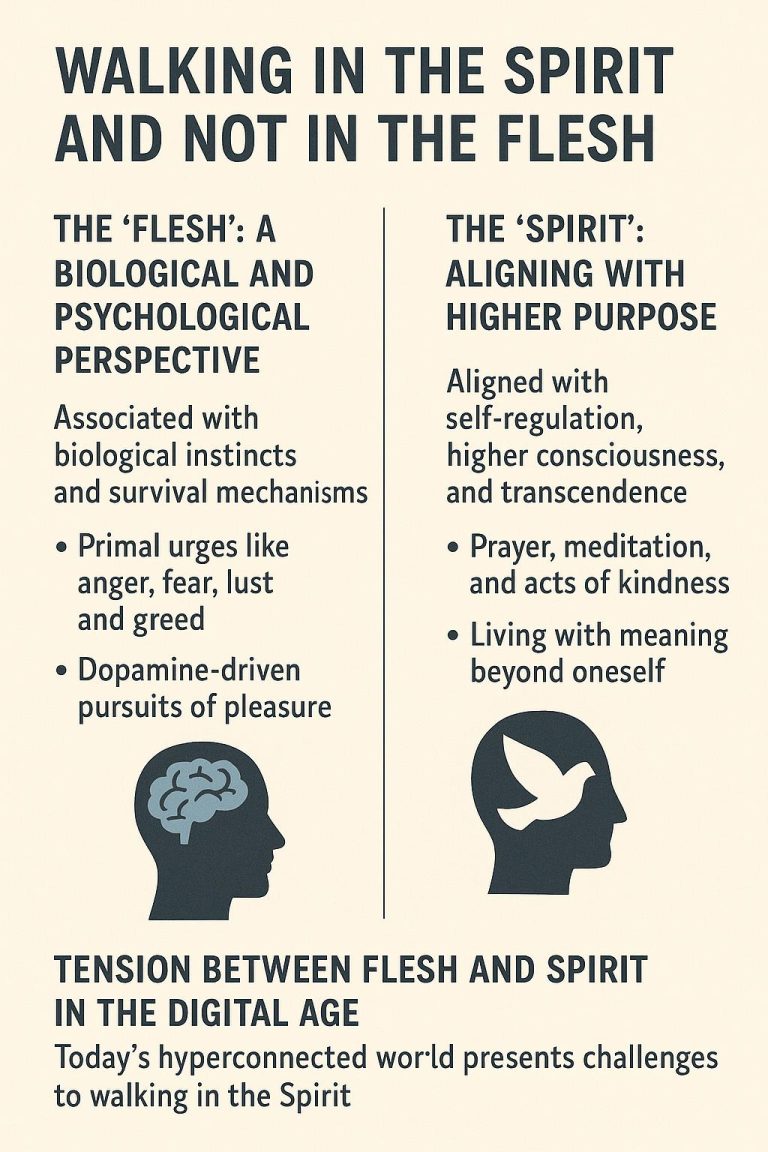

This perspective has force, but it also somewhat misses the question’s deeper thrust. The inquiry is not merely about which entity is real but about what kind of power we are ultimately reaching for when we build these machines. Even a secular philosopher might acknowledge that the ambitions embedded in our technological projects—to overcome death, to understand everything, to transcend our limitations—are recognizably religious in character. Quantum computing may be, in this sense, a secular attempt to grasp at divine attributes.

Power For What?

Perhaps the most illuminating way to approach this question is to ask: power for what? Divine power, as understood in most religious traditions, is not merely instrumental but intrinsically related to purposes beyond human comprehension—creation, redemption, the establishment of justice and love. The power of God, in Christian theology, is paradoxically revealed most fully in the weakness of the cross; in Jewish thought, it is inseparable from covenant and ethical demand; in Islam, it is always joined to mercy and compassion.

Quantum computing, by contrast, is purely instrumental. It has no purposes of its own, no values, no will. It is powerful in the way a hammer is powerful: capable of building or destroying depending on who wields it and toward what end. This is not a criticism but a clarification. The power of technology is always borrowed power—derived from human intention and directed toward human goals.

Conclusion

So what is more powerful: God or quantum computing? If God exists as classical theism describes, the question answers itself: the creator of all things is infinitely more powerful than any created thing. If God does not exist, then quantum computing is more powerful than a fiction—but this seems like a hollow victory, a category confusion masquerading as an answer.

Perhaps the wiser response is to recognize that the question reveals something about us: our longing for transcendence, our hope that our tools might deliver us from our limitations, and our persistent intuition that power itself requires some ultimate ground or source. Quantum computing is a testament to human ingenuity and a genuine expansion of our capabilities. But it is not God, and it does not pretend to be. Whether there is a God for it to be compared to—that remains the deeper question, one that no computer, quantum or otherwise, can answer for us.