Ex Nihilo Nihil: Nothing, Creation, and the God Who Makes All Things New

Introduction

The ancient axiom ex nihilo nihil fit—”from nothing, nothing comes”—stands as one of the most enduring principles in the history of Western thought. First articulated by Parmenides and later refined by Lucretius, Aristotle, and countless others, this principle asserts that being cannot emerge from non-being, that every effect requires a cause, that the universe does not yield something from absolute nothingness. Yet this seemingly straightforward claim has been wielded in remarkably different directions: by atheist philosophers to deny the possibility of divine creation, by economists and entrepreneurs to describe the laws of productive enterprise, and by Christian apologists to demonstrate the necessity of an eternal Creator. That a single principle can serve such divergent ends reveals both its profound importance and the need for careful examination. From a Christian perspective, properly understood, ex nihilo nihil fit does not undermine faith but rather points inexorably toward the God who alone transcends the causal order He has made.

The Atheist Deployment: Denying Creation

The materialist tradition has long employed ex nihilo nihil fit as a weapon against theism. The argument proceeds as follows: if nothing can come from nothing, then the universe cannot have been created from nothing. Matter and energy must therefore be eternal, having always existed in some form. There is no need for a Creator because there was never a moment of absolute beginning—only endless transformation of what has always been.

This reasoning found early expression in Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, where the Roman poet-philosopher argued that the gods, if they exist at all, play no role in the cosmos. Nature operates according to its own eternal principles, atoms combining and recombining through infinite time. The principle that nothing comes from nothing, in this framework, becomes a guarantee of cosmic self-sufficiency: the universe needs no external cause because it has always been.

Modern atheism has updated this argument with the language of physics. Some cosmologists propose that the universe emerged from a quantum vacuum—not true nothingness but a seething field of potential energy governed by physical laws. Others suggest eternal inflation, a multiverse, or cyclical models in which our universe is but one phase in an endless cosmic rhythm. In each case, the strategy is the same: avoid the need for a Creator by denying that there was ever true nothingness from which creation would need to occur.

From a Christian standpoint, this argument contains a subtle but fatal confusion. The atheist deploys ex nihilo nihil fit against creation ex nihilo, as though these phrases describe the same thing. But they do not. The philosophical axiom describes the behavior of finite, contingent things within the natural order: acorns come from oaks, effects from causes, new arrangements from prior materials. The Christian doctrine of creation ex nihilo, by contrast, describes the act by which the entire natural order—including the very principles of causation—was brought into being by a God who transcends that order.

To say that God created from nothing is not to say that “nothing” served as a kind of material cause, as though God reached into a void and pulled out a universe. It is to say that God alone is self-existent, depending on nothing outside Himself, and that everything else that exists does so because He wills it. The principle that finite things cannot emerge from nothing remains intact; what the Christian adds is that there exists One who is not a finite thing, not bound by the causal regularities He has established, and who therefore can be the ultimate source of all that is.

Business Causality: The Economy of Nothing

Far from the halls of metaphysics, the principle ex nihilo nihil fit finds surprisingly robust application in the realm of commerce and enterprise. Here, the axiom translates into a practical truth: value does not appear spontaneously. Wealth must be created through the combination of labor, capital, raw materials, time, and ingenuity. There is no economic free lunch; every output requires input.

This principle disciplines the imagination of the entrepreneur. A successful business cannot be conjured from wishes or built on nothing but enthusiasm. It requires investment—of money, certainly, but also of skill, relationships, knowledge, and relentless effort. The would-be founder who imagines that a clever idea alone will generate prosperity learns quickly that ideas must be incarnated in products, services, teams, and systems. The gap between conception and execution is vast, and crossing it demands real resources.

Moreover, ex nihilo nihil fit exposes the hollowness of economic schemes that promise something for nothing: Ponzi structures, speculative bubbles, and fraudulent enterprises that create the illusion of wealth without underlying value. Such schemes inevitably collapse because they violate the fundamental grammar of economic reality. Value must come from somewhere. When it appears to emerge from nothing, we are witnessing not creation but redistribution—or, more often, theft.

From a Christian perspective, this economic application of the principle carries both affirmation and warning. The affirmation is that work matters. The creation mandate in Genesis—to till the garden, to exercise dominion, to be fruitful—presupposes that human beings participate in the ongoing work of bringing order from chaos, value from raw potential. We are not called to passive existence but to creative labor, and this labor requires real investment of self. The parable of the talents condemns the servant who buried his master’s money; faithful stewardship means putting resources to work, accepting risk, and generating increase.

The warning is against the idolatry of wealth and the illusion that economic causality is the only causality that matters. If nothing comes from nothing in the economic sphere, we might be tempted to conclude that everything we have is purely the product of our own effort—that we are self-made, owing nothing to God or neighbor. But this conclusion forgets that our very capacity to work, to think, to create, is itself a gift. The raw materials we transform were not made by us. The stable social order that allows commerce to flourish is sustained by forces beyond any individual’s control. Even our next breath is not guaranteed by our labor. The Christian businessperson, therefore, holds success with open hands, recognizing that all good gifts descend from the Father of lights.

The Cosmological Argument: Proving the Creator

Yet it is in natural theology that ex nihilo nihil fit finds its most profound application—not as a denial of God but as a signpost pointing toward Him. Here, the principle becomes the engine of the cosmological argument, one of the most ancient and enduring demonstrations of God’s existence.

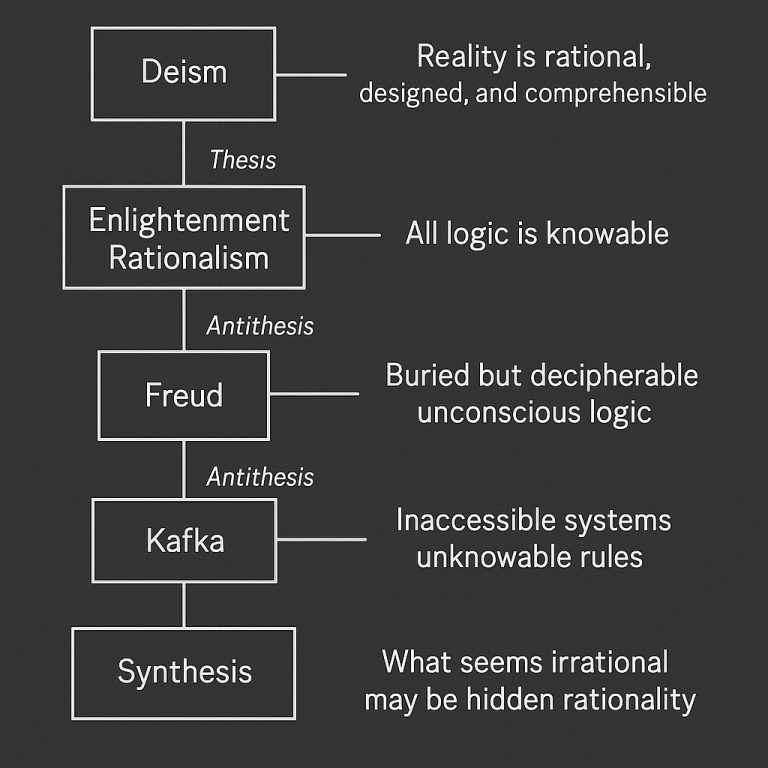

The argument proceeds from the observation that contingent things exist—things that might not have been, that came into being and will pass away, that depend for their existence on other things. A tree depends on soil, sunlight, water, and seed. The seed depended on a prior tree. The sun depends on gravitational collapse and nuclear fusion. And so the chain extends backward. But can this chain extend infinitely? Can there be an endless regression of contingent causes, each depending on another, with no foundation beneath?

The cosmological argument answers no. An infinite regress of contingent causes explains nothing; it merely postpones explanation forever. If every link in a chain is itself suspended from another link, and there is no anchor, then the entire chain hangs from nothing—which is to say, it cannot hang at all. Ex nihilo nihil fit demands that the chain of causes terminate in something that is not itself caused, not contingent, not dependent on anything external. There must be, in Aquinas’s language, a First Cause, or in Leibniz’s framing, a Sufficient Reason for the existence of anything at all.

This First Cause cannot be merely another item in the series of natural causes. It must be radically different: self-existent, necessary, eternal, and possessed of the power to bring contingent beings into existence. It must be, in short, what classical theism means by “God.”

Notice that this argument does not violate ex nihilo nihil fit but rather honors it to the uttermost. Precisely because nothing comes from nothing, there must be Something that is not nothing—a necessary Being who has existence in Himself and shares it with creatures. The principle that seemed to threaten creation doctrine turns out to require it. The atheist who wields this axiom against God finds that, rightly understood, it cuts the other way entirely.

The Christian adds to this philosophical demonstration the revelation of Scripture. The God discovered at the end of the cosmological argument is not merely a metaphysical abstraction, a First Cause and nothing more. He is the living God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the One who declares “I AM WHO I AM” and in so doing identifies Himself as Being itself, the ground of all that exists. He is not only the cause of the world’s existence but its sustainer moment by moment, holding all things together in Christ, in whom all things were created and for whom they exist.

Nothing and the New Creation

There is one final dimension to this meditation that a Christian cannot overlook. The God who created all things ex nihilo is also the God who makes all things new. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is, in a profound sense, a second creation—the bringing forth of new life from the nothingness of death, the defeat of the ultimate negation, the empty tomb that declares that God’s creative power is not limited by any void.

Here, ex nihilo nihil fit meets its glorious exception—or rather, its glorious confirmation. For it remains true that nothing comes from nothing within the created order. Death leads only to death; entropy marches toward dissolution; the grave is the terminus of natural causality. But God is not bound by the created order. The same power that spoke light into darkness and being into non-being speaks life into death and hope into despair. Christ is risen, and in His rising, the principle that nothing comes from nothing is not violated but transcended. God does not conjure life from a void; He is Life itself, and death cannot hold Him.

This is the deepest meaning of creation ex nihilo for Christian faith. It is not merely a doctrine about the distant past, about how things began billions of years ago. It is a confession about the character of God and the nature of His ongoing relationship with the world. The God who created from nothing is the God who can redeem from nothing, who can take our failures, our emptiness, our sin, our death, and bring forth new creation. “Behold, I am making all things new.”

Conclusion

Ex nihilo nihil fit is a principle that has been used to deny God, to describe economic reality, and to prove the necessity of a Creator. That it can serve such varied purposes testifies to its fundamental importance in human thought. But for the Christian, the principle finds its true home in the doctrine of creation. Precisely because nothing comes from nothing within the finite order, there must be One who transcends that order—the self-existent God who alone has life in Himself and who, in sovereign freedom, gives existence to all that is.

The atheist use of this principle is self-defeating, for it demands what only God can provide: an ultimate ground for the existence of contingent things. The economic application is instructive, reminding us that value requires real investment even as it warns against the idolatry of self-sufficiency. But the cosmological argument reveals the principle’s deepest truth: that the universe is not self-explanatory, that causation must terminate in a necessary Being, and that this Being is none other than the God and Father of Jesus Christ—the One who creates from nothing, sustains all things by His word of power, and even now is making all things new.